Victim of an arrest warrant issued by the Turkish authorities, the Turkish journalist Can Dündar, while at the Internazionale festival in Ferrara to be honoured by the Anna Politkovskaja journalistic award, was secretly exfiltrated to Germany – where Dündar benefits from political refugee’s status – to avoid being arrested by the Italian police. Such Interpol’s international arrest warrant raises a double problem: the first is the abusive use of Interpol for purely political ends and the absence of means to avoid such abuse, the second is the absence of protection of persons, benefiting from Political refugee’s status in one EU country, when present in other member countries. The Dündar’s case is unfortunately not unique.

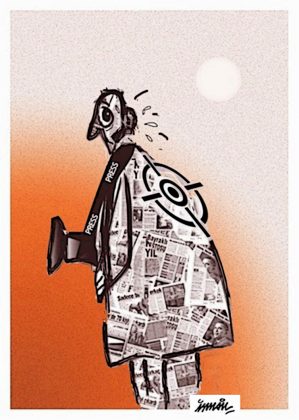

On 29 September night, the Turkish journalist, Can Dündar, a political refugee in Germany, was in Ferrara (Italy) to receive the Anna Politkovskaja award. The Anna Politkovskaja journalist prize (https://www.internazionale.it/festival/premio) was created in 2009 by the weekly magazine Internazionale, to commemorate the Russian journalist killed in Moscow in 2006, with the aim of supporting the commitment and the courage of reporters who have distinguished themselves in the world for their investigations. The award is presented each year during the “International in Ferrara” festival (https://www.internazionale.it/festival). Together with my friend Ismail Dogan, a Belgo-Turkish cartoonist and an opponent of Erdogan, who too was invited to the festival, we had a friendly conversation with Can Dündar (Photo) without imagining what was on course. During the night, Dündan and Internazionale were informed of an arrest warrant issued by Interpol against the journalist. Such a mandate obliges the police of any member countries of Interpol to proceed to the arrest of the person identified in the “red notice”, name in the Interpol jargon of these arrests warrants.

On May 6, 2016, Can Dündar while entering the Tribunal of Istanbul, six months after being arrested, to hear the sentence against him, was approached by a man who shot him. Dündar remained unharmed, but once he entered the court he received the news of being sentenced to five years and ten months of jail for “espionage and disclosure of state secrets“. His colleague Erdem Gül was sentenced in the same time. At the time of his arrest, Dündar was running the opponent Cumhuriyet newspaper to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. He was targeted by the authorities because he had published an article in which he claimed that the Turkish secret services, in January 2014, had delivered arms to the Syrian rebels who fight against President Bashar al Assad. He managed to escape from his country and, since June 2016, he lives in exile in Germany, where he founded the information site Özgürüz (We are free). https://ozguruz.org/tr/2017/02/13/ozguruz-basin-bulteni-13-02-2017/

He thought to be safe in the EU, protected by his political refugee status in Germany. If Germany actually was protecting him, it might not have been the case in other countries. In fact, it is not the first time Erdogan has used Interpol to arrest political opponents, journalists or writers. During the summer, Erdogan had launched two arrest warrants against opponents present in Spain: on 19 August 2017, against the 60-years-old and a German citizen since 2002, Dogan Akhanli, an avid critic of Erdogan, who writes about human rights in Turkey; on August 8, 2017, against Hamza Yalçin, a 59-year-old journalist, with a double Turkish and Swedish nationality, who was arrested at Barcelona airport. In both cases, the protests and the swift action of the Swedish and German authorities (both arrested had European nationality, even if of Turkish origin) made it possible to avoid their extradition.

This abuse of international police cooperation through Interpol (https://www.interpol.int) is frequent and poses a real problem for both democracies and freedom of press and expression. And Turkey is not the only country to abuse it. Other regimes do not hesitate to use it to arrest political opponents, dissidents and journalists, such as China or Azerbaijan (arrest and extradition of the Israeli-Russian journalist Alexandre Lapshin at Minsk airport in 2016 who was sent to Bakou where he was condemned to 3 years of jail). Obviously, it also poses the problem of the democratic and judicial control of Interpol’s activity. Chaired by the Chinese Meng Hongwei, former director of the Chinese secret police, and despite the fact that the general secretary is the German Jürgen Stock, Interpol is late to make the necessary reforms to combat the abusive use of arrest warrants or to allow the rapid recourse by victims of such abuse.

The example to follow could be Europol, the body coordinating the European police (https://www.europol.europa.eu), which, unlike Interpol, is monitored by a democratic authorities: its budget must be approved by the the European Parliament and parliamentarians also have a say in high-level appointments. Furthermore, the European Court of Justice carries out judicial control over the work of Europol. Such changes, which Interpol’s communication service claims to be under way, would require strong political action – at least by Western democracies. However, Interpol regroups 190 countries, which not all are in favour of such reforms.

So, obviously, we can think that a strong action at the European level would be essential and urgent, at least to prevent a Member state from making arrests and extradition of persons with dual nationality, political refugees status or known dissidents of regimes, especially when such situation is known, particularly in countries like Turkey. According to Reporters Without Borders (https://rsf.org), up to May 2017, the Turkish authorities closed 140 media, jammed 700 press cards, and imprisoned more than 100 journalists. On 15 May, Oguz Güven was the twelfth journalist of the opposition newspaper Cumhuryet (the newspaper that Can Dündan was heading) to be imprisoned. In the RSF ranking, Turkey is in 155th place out of 180, in the world ranking of freedom of the press (#RSFIndex – https://rsf.org/en/ranking) and … Italy in 52nd place, closer to Poland (54th) and Hungary (71th), than to Germany (16th) or France (39th).

This battle would deserves a real political commitment both in the various European countries and at the level of the EU. It doesn’t seems to be a priority, I’m afraid.

Here is the video message that Can Dündar delivered to students to who he should have deliver a speeche on September, 30 dealing with freedom of Press in Turkey: VIDEO-DUNDAR-fhd